An officer is working patrol when they observe a stolen vehicle turning in front of them, from a side street. The officer confirms with dispatch the vehicle is stolen and follows it as he waits for additional units to conduct a high-risk traffic stop. Prior to the arrival of back-up units, the stolen vehicle pulls to the curb. The driver, and sole occupant, exits the vehicle holding a weapon and flees towards a residential neighborhood. While fleeing the suspect’s hat falls to the ground. The officer gives chase but quickly loses sight as the suspect jumps multiple fences.

Now that the driver has fled, the officer requests the assistance of a K9 Team in order to conduct a safe and systematic search of the area.

While working as a custody supervisor, a Police officer directs deputies to relocate an inmate from his cell to a disciplinary cell. The man has an amputated leg and was issued a wheel chair and a prosthetic leg by medical staff. He objects to the movement and boards up in his cell, forcing the officer to organize the Special Operations Response Team to do a cell extraction. By the time the officer and their team enter the section and reach his cell, he has removed all items for boarding up and is sitting in his wheel chair with his hands raised and is complying with the officer's orders. The officer's deputies handcuff him and stand him on his one leg. Instead of using his wheelchair, the officer direct's him to hop to the disciplinary cell which is 64 feet away. When he does so, his leg gives out and he falls. The officer directs their deputies to pick him up by his handcuffed arms and carry him the remainder of the way.

This post is offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers than the law requires. Scenario: An officer pulls over a vehicle for running a stop sign and speeding. When the officers contact the driver, they ask if he is on probation or parole. He admits he is on parole. The officer conducts a parole search of the vehicle and finds the subject has a firearm. Was it a violation of his 4th amendment rights for the officer to ask the subject's parole status? Answer: The 9th Circuit Case United States V. Ramirez from 2024 answers this question. In this case, the court said, “Asking someone about his parole status is substantially similar to running a criminal history check during a traffic stop—a practice that we have held passes muster under the Fourth Amendment. Indeed, a person's criminal history and parole status are inextricably intertwined such that running a criminal history check will, in many jurisdictions, reveal a person's parole status. If anything, parole status may reveal more about potential danger than a criminal background check: a parolee has committed a serious enough crime to warrant prison time and has likely been released recently, while a criminal history check may yield a stale history of minor offenses committed years ago. " So, when an officer pulls a subject over you can inquire about parole status. If the subject turns out to be on parole, the officer may in turn search them. This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

This post is offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers than the law requires. Scenario: An officer is working in a custody facility and has to move a large number of inmates by themselves. What precautions for their safety and the safety of the inmates should they take for such a task? Answer: This is not the time to make phone calls or text your significant other. This is a very dangerous time because you could be significantly outnumbered depending on the department's policy on inmate-to-officer ratios. Some things an officer can do to mitigate the danger are: 1. Walk toward the middle or rear of the inmates, keeping them on the opposite wall from the officer. This will help keep an eye on the whole group. 2. Keep their head on a swivel. Do not get distracted by anything. The officer's eyes and ears should be dedicated to the group of inmates and the area around them. 3. Don’t let the inmates bait the officer into a conversation. Engaging an officer in conversation might be a tactic that's used to distract them from nefarious behavior, including plans to assault the officer or another inmate. Tell inmates to hold their conversation, and you'll speak with them as soon as you arrive at your destination. 4. Officers can Communicate movement throughout the facility. Make sure everyone knows where they are coming from and where they are going and use plain language for places that are not normally described in their everyday movement. Remember that just because an officer has moved inmates on several other occasions without incident, doesn’t mean they will be safe this time. This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

A Police officer is working as a uniformed patrol officer responding to a call of an argument between multiple roommates. As the officer speaks to one of the involved subjects inside the house, they receive information that the reporting party saw one of the roommates brandish a black handgun and yell out a death threat. The officer also hears a scuffling noise in the back room.

Can the officer conduct a protective sweep of the apartment for the armed subject?

Scenario: An officer is working patrol when they encounter a subject that is visibly upset and possibly intoxicated. Upon further inspection, the officer notices several open wounds consistent with self-harm.

Does the officer have enough probable cause to detain the person and take them to the hospital per Welfare and Institutions Code 5150?"

On TV, you have no doubt seen a legal drama where the suspect pleads not guilty by reason of insanity. But does that really happen in the real world?

The answer is yes. When a subject does plead not guilty by reason of insanity, incompetent to stand trial or a mentally disordered offender, they are usually sentenced to time in a state hospital or prison. But what happens to those types of criminals when they are released?

This post is offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers than the law requires. Scenario: While working patrol, a Police officer encounters a crime victim in crisis. The officer knows they are in crisis based on the previous videos they've watched on this topic. What is another action the officer can take to help them through this difficult time? Answer: California POST suggests communicating to the victim what exactly will happen next. Explain exactly what procedures and follow-up will be required next. Also, explain why the follow-up is important and what the result could be. An example of this is telling the victim of a sexual assault the steps you will take in the investigation, including all of the medical examinations they will need to go through and why they are important. Giving the victim an explanation can help them through their feelings of helplessness. This can also give them a sense of control in an out-of-control situation. Be sure to end by making sure you have answered any questions they still have as well. This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

While working patrol, a police officer sees a known gang member at a local gas station. The officer sees that his vehicle doesn't have a front license plate. The officer parks and waits for him to drive away. While they wait, the officer calls a K9 officer and has him start heading their way. When the gang member drives away from the station, the officer conducts a vehicle stop a short distance away. The police officer notifies him that they stopped him for not having a front license plate and then they begin to write the citation. While writing the citation the K9 arrives, sniffs around the car and hits on the sent of burnt gun powder. The officer abandons their citation, searches the vehicle and locates a firearm in the center console.

Will the firearm evidence be dismissed because the officer conducted a pretextual vehicle stop in violation of California Vehicle Code 2806.5?

An officer is working custody when BAM, there’s an illness outbreak. To try to mitigate the outbreak, the officer and other officials decide to move several inmates from one facility to another.

Can the officer be held liable if the inmates at the facility the sick inmates were moved to become sick?

While working patrol, an officer wants to make consensual contact with someone who's standing on a street corner with known drug activity.

Since the officer doesn't have any reasonable suspicion that they're involved in a crime, what steps can the officer take to ensure the contact remains consensual?

An officer working in custody, and an inmate tells them that another inmate threatened his life. He asks to be moved from his current housing unit and the inmate to be put on a “keep away” list. The officer reports it to their supervisor and the two of them determine that there is a basis to move him but a keep away was not established. Then, the inmate who was threatened is out for movement within the facility and is attacked by the other inmate, causing serious injury.

Patrol officers and detectives from an agency's gang suppression unit respond to call that a group of young men are filming a music video in a parking lot and one of them, who's described as thin, wearing all black and approximately 17 years old, is waiving a gun around. This is a known gang area in your city.

When the officer arrives, a person matching the description of the person with the gun runs. Detectives catch him and locate a firearm on his person. Subsequently the detectives decide to detain everyone on scene. One adult male named Mosely, is handcuffed, patted down for weapons, then detained inside the front passenger compartment of a patrol vehicle. Detectives ask Mosely twice for consent to search his vehicle but he declines. Detectives search it anyway and locate a firearm in his car, leading to his arrest.

An officer is working patrol when they get a call about a robbery involving a firearm. When the officers arrive, they contact the victim, who begins to tell them about the crime, however, the officer notices they are shaking pretty vigorously, they are staring off into space while talking to the officer, and they are sweating profusely. Does the officer recognize the signs that the victim may be experiencing a crisis?

This post is offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers than the law requires. Scenario: An officer is in a caravan of several patrol vehicles, canvassing a high crime area known for narcotics. The intent of the caravan is to locate narcotics sales, drug customers, and lookouts. As the officer canvasses, they observe a male subject, standing alone, holding a bag. As soon as the subject sees him, he immediately flees. Can the officer give chase and detain the man to investigate further? Answer: This scenario is similar to the 2000 United States Supreme Court Case of Illinois v Wardlow. The court explained: “...an officer may, consistent with the Fourth Amendment, conduct a brief, investigatory stop when the officer has a reasonable, articulable suspicion that criminal activity is afoot. While "reasonable suspicion" is a less demanding standard than probable cause and requires a showing considerably less than preponderance of the evidence, the Fourth Amendment requires at least a minimal level of objective justification for making the stop.” The court then went on to explain: “In this case, moreover, it was not merely respondent's presence in an area of heavy narcotics trafficking that aroused the officers' suspicion, but his unprovoked flight upon noticing the police. Our cases have also recognized that nervous, evasive behavior is a pertinent factor in determining reasonable suspicion.” “Headlong flight—wherever it occurs—is the consummate act of evasion: It is not necessarily indicative of wrongdoing, but it is certainly suggestive of such. In reviewing the propriety of an officer's conduct, courts do not have available empirical studies dealing with inferences drawn from suspicious behavior, and we cannot reasonably demand scientific certainty from judges or law enforcement officers where none exists. Thus, the determination of reasonable suspicion must be based on commonsense judgments and inferences about human behavior.” "...officers are not required to ignore the relevant characteristics of a location in determining whether the circumstances are sufficiently suspicious to warrant further investigation." "We conclude (the officer) was justified in suspecting that (the man) was involved in criminal activity, and, therefore, in investigating further." So in your case, you can use your commonsense judgment and inferences about human behavior to support your reasonable suspicion stop of the fleeing subject. An officer who works in California might be wondering what the difference is between this US Supreme Court Case and the California Supreme Court Case of People v. Flores where the suspect ducked behind a car when he saw the police. The California Supreme Court discussed the difference in Flores by saying: "Flores’s disinclination to engage with the officers does not carry the same salience as headlong flight in the totality of the circumstances analysis. His acts of ducking out of sight, bending with his hands by his shoe, and not acknowledging the officers’ presence, suggest an unwillingness to be observed or interact. But they are not the “consummate act of evasion.” Police officers should remember to articulate facts, observations, and their perspective leading up to any detention. If you have any further questions or concerns about this case, please refer to the entire case which is provided in the additional resources section of the lesson in you TheBriefingRoom.com Subscription and also your agency's policy, which can be more restrictive on officers than the law requires. This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

This post is only offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers that the law requires. Scenario: While working patrol, an officer legally detains a juvenile in the parking lot of a movie theater. After the officer gets consent to search her backpack, they discover the juvenile has an unloaded firearm that's registered to her parents. Is there any circumstance under which the juvenile can lawfully possess a firearm in California? Answer: According to California Penal Code Section 29610(c) says: “Commencing July 1, 2023, a minor shall not possess any firearm.” However, Section 29615 lists several exceptions to this which require the juvenile either be accompanied by a parent, guarding or responsible adult or has their permission. They also must be in direct transit to or from a lawful recreational sport or activity or be on lands owned by their parent or guardian. You can find those exceptions listed in their entirety in the additional resources for this video. This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

This post is only offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers that the law requires. Scenario: While working patrol, an officer responds to a vandalism call. When they arrive, a shop owner says that they observed another person vandalizing the front of their store. That person is still present and the shop owner wants that person arrested for the misdemeanor crime. Is the officer required to accept the citizen's arrest regardless of the evidence that they find and what liability exists in making the wrong decision? Answer: Unfortunately, this scenario is made complicated by a series of case and statutory laws that each address individual aspects of this issue. In 2005, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals sought to clarify this issue by summarizing the law around citizen's arrests in a case called Meyers v. Redwood City. In that case, the court said, "California law gives the officer the choice of making the citizen's arrest or not, but there are powerful incentives to make the arrest. On the one hand, an officer who makes an arrest pursuant to a citizen's complaint is not subject to liability for false arrest or false imprisonment. CAL. PENAL CODE § 847(b)(3). On the other hand, an officer does not have to effect the arrest if he or she "is satisfied that there are insufficient grounds for making a criminal complaint[.]" CAL. PENAL CODE § 849(b)(1). However, there is a catch: If it turns out that there were grounds for the complaint and the officer failed to take the suspect into custody, the officer is subject to fines or imprisonment. CAL.PENAL CODE § 142(a). The California courts have held that even though an officer may decline to take a suspect into custody under Section 849 if he finds no grounds for the complaint, an officer cannot be sued civilly if he makes the arrest and, it turns out, there were no grounds for the citizen's arrest." On these calls, its important to do thorough investigations beyond just listening what the victim has to say. This includes looking for physical and video evidence and speaking to witnesses. If there isn't probable cause for the arrest or its clear the person did not commit the crime they're being accused of, officers are not required to accept the citizen's arrest. But, if there are reasonable grounds for the citizen's arrest and the officer fails to accept the arrest, the officer may be subject to fines or imprisonment. As always, the resources mentioned in this training are available in the additional resources section of your TheBriefingRoom.com Learning Platform and officers should make sure to refer to your agency policy which can be more restrictive on officers than the law requires. This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

A Police officer is backing up their partner on a traffic stop in an area known for gang activity. The officer's partner discovers that the backseat passenger is on parole and conducts a parole search of the vehicle. While conducting the search, the partner uses the ignition key to unlock the locked glove box and finds a loaded firearm.

Was the search of the locked glove box based on the backseat passenger's parole status lawful?

This post is only offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers that the law requires. On July 18, 2024, an update added to computer systems caused a worldwide outage of many operating systems, including the most widely used system, Microsoft. During the outage, computer programs were unusable for law enforcement agencies nationwide. Do you know how to get around your city should an outage like this happen again? Law enforcement today relies heavily on technology to be able to function, whether it's for navigation or information. The problem is, if an outage occurs, crime continues and we must still be able to do our jobs. Some things officers can do to prepare are: 1. Know how to get around your beat area without digital maps. This can include having physical maps readily available, including Thomas Guide, which is still available for purchase online. 2. Always carry a notebook so you can write calls down if the computer is unavailable. 3. Have fully charged batteries and a full tank of gas 4. Know your agency’s plan and policy for emergency operations. Remember, you can still get the job done as long as you plan for any situation. What would you and your shift do in case of an outage? This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

While working patrol, an officer and their partners get into a fight with a violent arrestee and finally get handcuffs on him. He's still flailing around after being handcuffed so the officer continues to put bodyweight on the man and tell him to calm down. He claims he can't breathe and the officer tells him that if he's fighting and yelling, he can still breathe. The man later claims that he received two fractured vertebrae and has ongoing numbness due to your actions.

Can the officer be held liable for excessive force for their actions?

An officer is working in a custody facility when they see a couple of inmates that appear very drunk. The officer doesn't smell Pruno but the officer does a search anyway. During that search, the officer discovers a Styrofoam cup that smells like pure alcohol and sees reddish residue.

Is there another type of jail-made alcohol besides Pruno?

An officer and their partner detained a gang member for potential trespassing at an apartment complex. The officer's partner conducted a pat down for weapons and discovered a key fob on the man's belt loop. This is odd because he said he didn't have a vehicle. The partner removed the key fob from the man's belt and he intentionally pushed the lock button several times, causing the headlights on a nearby vehicle to flash. Suddenly, the man fled but the officer caught and arrested him. After he was arrested, the officer's partner went to the vehicle, saw the butt end of a handgun sticking out from under the seat and conducted a warrantless search of the vehicle. The handgun was seized and it was discovered that it was previously used in a robbery.

An officer is working as a custody officer in a county jail. An inmate worker approaches the officer and starts talking about what he does for work on the outside. The officer lets it slip that they need some work done on their house and he lets them know he has a friend that can do the work for cheap.

While conducting random license plate checks, an officer receives information from dispatch that there is a misdemeanor arrest warrant attached to one of the vehicles that just passed them. The officer conducts an investigative stop and discovers the wanted person is not in the vehicle.

Can the officer be held liable for unlawful detention?

While working patrol at 4A.M., an officer receives a call from an anonymous person saying that two people were behind a local business "scoping the place out." The officer arrives at the location and sees an occupied vehicle across the street. The officer orders the driver to walk backwards to them and handcuff him while he's down on his knees. A short time later, the officer discovers he's a newspaper delivery driver and not involved in any crime, so they let him go.

Did the officer violate his constitutional rights by detaining him?

This post is only offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers that the law requires. Scenario: A Police officer is working patrol when they get a call of a man carrying, what looks like, a shotgun. The officer arrives on scene and recognizes the suspect from prior calls and know he suffers from mental health issues. During the officer's attempts to de-escalate, he tells you the gun is just a BB gun and tries several different things to prove it's fake. If he points it at the officer, can they still use deadly force? Answer: This question was answered in the 2023 9th Circuit Court of Appeals case Estate of Strickland v Nevada County. In this case, the officers ultimately used deadly force, killing the suspect. The court said, “The pivotal moment occurred when (the suspect) began pointing the replica gun in the officers' direction. At that point, they had "probable cause to believe that [the suspect] pose[d] a significant threat of death or serious physical injury" to themselves and it became objectively reasonable for them to use lethal force.” The court even supported the officers’ decision to use deadly force though the gun had an orange tip and the suspect tapped the side of the gun and it made a plastic sound. While it was reasonable to believe that the gun posed a threat of death or serious bodily injury, the officers also tried to slow the pace of the interaction and articulated clearly that they did not believe the gun was fake. The Court said, "While the misidentification of the replica gun adds to the tragedy of this situation, it does not render the officers' use of force objectively unreasonable." This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

A Police officer is working patrol when they respond to a group of people assembling at an intersection. They start to increase in number as the officer shows up and begins to impede traffic by standing in the roadway.

Can this be considered an unlawful assembly, or is this act protected under the 1st Amendment?

This post is only offered as a discussion topic only and does not represent legal advice. Officers must refer to the laws in their own State as well as their agency's policies, which can be more restrictive on officers that the law requires. Scenario: A witness called dispatch and reported that two people on bicycles were possibly casing by shining flashlights into parked vehicles. A Police officer and their partner arrived and the partner detained a man simply because the man was sitting in his vehicle which was parked in the vicinity of the call. After detaining the man, the partner learned he was on parole, conducted a search and located contraband. Was the detention and search of the man legal and is the evidence admissible in court? Answer: This scenario is similar to the 2023 California Supreme Court case People v McWilliams. In this case, the court ruled that the detention was unlawful and the contraband located was not admissible in court. The court explained, “As a general rule, evidence seized as a result of an unlawful search or seizure is inadmissible against the defendant in a subsequent prosecution.” The court further stated, “We conclude the officer's discretionary decision to conduct the parole search did not sufficiently attenuate the connection between the officer's initial unlawful decision to detain McWilliams and the discovery of contraband.” So, because there was no reasonable suspicion that connected the man who was detained to any crime, the detention of the man was unlawful. Therefore, everything that happened after that unlawful detention was not admissible, even though the man was on parole. Nothing in this incident would prevent officers from doing a consensual contact, asking the man questions and then detaining him after discovering he was on parole. But before an officer decides to detain a person, you must have reasonable suspicion that they were, are, or are about to be involved in criminal activity. Just being in the area of a reported crime is not enough. And by the way, this is different than discovering someone has an arrest warrant after an illegal detention. The California Supreme Court has allowed the admission of evidence seized incident to arrest on a valid warrant, where the warrant was discovered during an unlawful detention - "People v. Bendlin (2008, Cal Supreme Court). The difference being that a warrant is a judicial mandate to arrest, whereas a parole search is discretionary on the part of the officer. As always if you are a subscriber to TheBriefingRoom.com, you can find this case in its entirety in the additional resources. Officers should always make sure to refer to their agency policy, which can be more restrictive than the law requires. This blog topic serves as a summary of our video lesson on this crucial topic. If you're interested in accessing the full video lesson and additional resources, click the link to register for your free 30-day trial.

A Police officer is working as a custody officer when inmates on the outside work crew they are overseeing ask to return to the custodial facility to participate in a religious service. Moving these inmates at different times than the rest of the work crew would cause significant security risks including a lack of security to oversee the inmates and the creation of a special group of inmates that would be treated differently than everyone else. If the officer doesn't bring them in for the religious service, is it a violation of their 1st Amendment Right to freely practice their religion?

A uniformed police officer is making an arrest at a store when the suspect begins to fight. The officer asks one of the security guards to help you force the man into custody. If that security guard helps the officer, is he subject to all the same rules surrounding use of force that a police officer must follow?

A police officer is outside a residence investigating a report of a potential kidnapping in progress, and sees a person matching the suspect's description standing inside the home. The officer tries to enter the house without a warrant due to exigent circumstances but a family member stands in front of the door to block them from going inside.

While working patrol, dispatch told an officer a mentally ill man called 911 and reported that there were people outside of his apartment with a saw. When the officer arrived, the man refused to answer the door and only made random statements through the door. After two minutes of back and forth discussion, he stepped out of his apartment with a metal pipe in his hand

An officer is working as a custody officer when they receive a grievance from an inmate. As they read through the grievance, the officer notices the grievance is particularly insulting to a specific co-worker and the language feels threatening.

Can an officer deny the grievance and refuse to send it through the process?

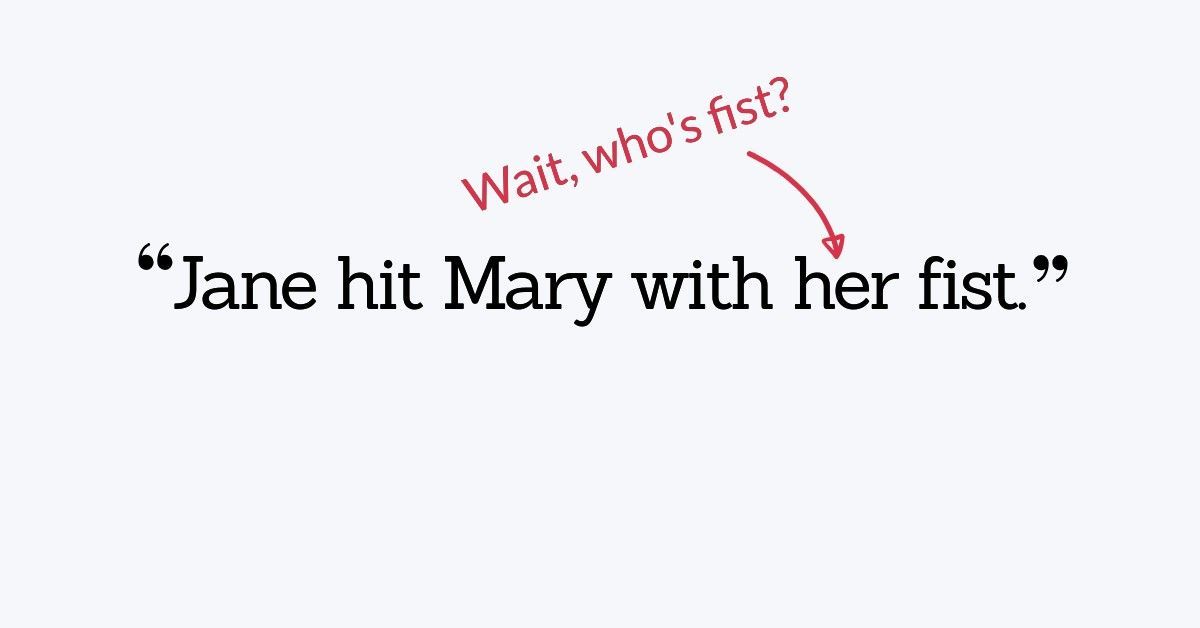

As a Police sergeant, have you ever read a report describing the actions of multiple people and been unable to tell which subject in the report was responsible for the actions mentioned? Well, an officer can avoid that confusion in their own reports by understanding the correct use of possessive pronouns.